Back in 2018 I wrote about finding my second great-grandmother, Nancy J. Whitney, in the 1850 census and the immediate question that followed:

Who was her mother?

At the time, the census seemed to offer a straightforward answer. With the addition of DNA and Ancestry’s ThruLines®, I expected that question to finally be settled.

It wasn’t.

Instead, the combination of census records, a single marriage record, and a series of land transactions has created one of the most instructive conflicts in my research—and a perfect example of why no single source should ever stand alone.

What ThruLines Does — and Does Not — Tell Me

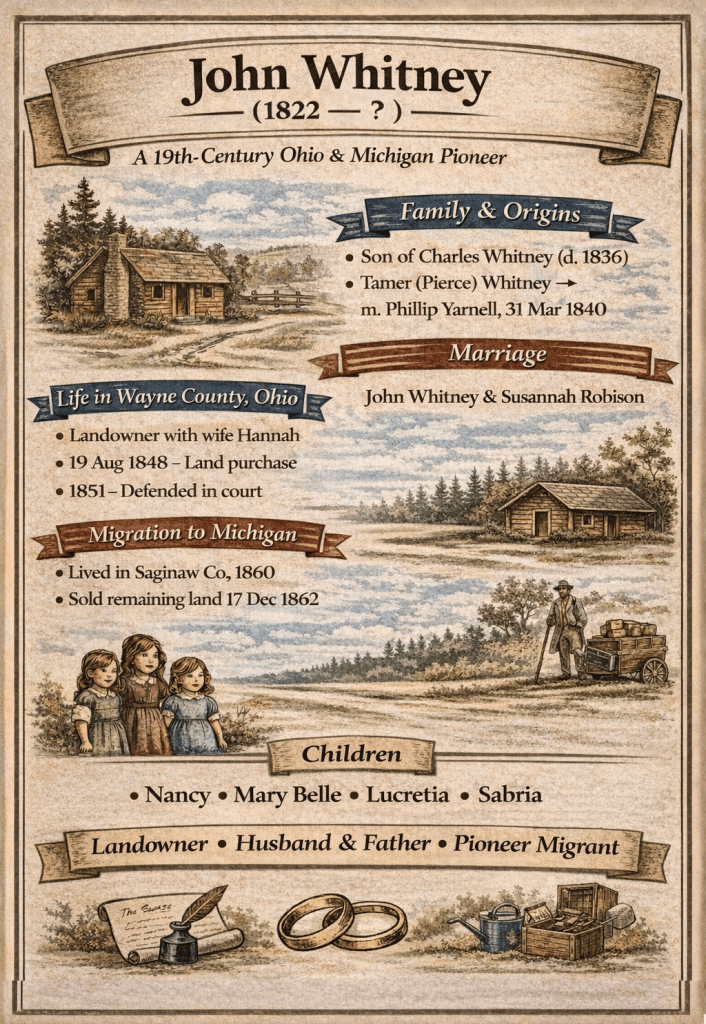

ThruLines confirms my descent from John Whitney.

It does not identify a wife for him.

It does not suggest a mother for Nancy.

It does not offer a second pathway through another marriage or through a different set of descendants.

In this case, ThruLines is doing exactly what it is designed to do—it is confirming a line. It is not resolving a documentary conflict.

And that silence is important.

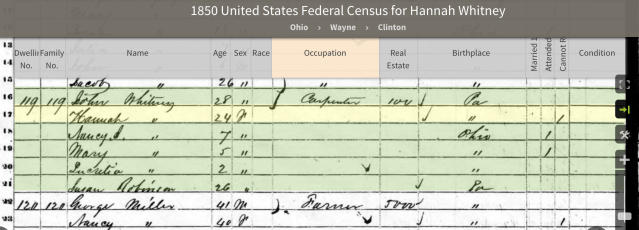

The 1850 Census: A Household with Two Adult Women

The 1850 census for Wayne County, Ohio, shows the household of John Whitney as:

- John Whitney, 28

- Hannah, 24

- Nancy, 7

- Mary Belle, 5

- Lucretia, 3

- Susannah Robison, 26¹

The census does not state relationships in 1850. Any identification of a spouse is based on the common pattern of enumeration, not on an explicit statement.

What is clear is that Hannah and Susannah are two separate individuals. They have different given names, different ages, and Susannah is listed with the surname Robison rather than Whitney.

Whatever their roles in the household, they are not the same person.

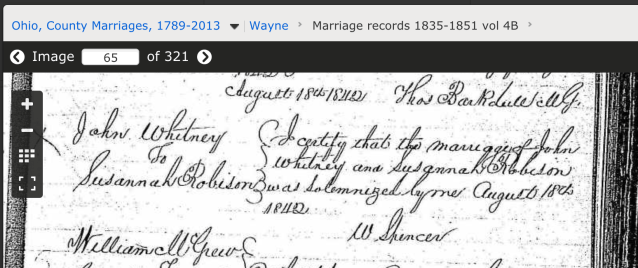

The Marriage Record That Complicates Everything

There is one—and only one—marriage record for John Whitney in Wayne County:

John Whitney to Susannah Robison, 18 August 1842.²

Nancy’s 1843 birth fits this marriage perfectly.

If this were the only record, the conclusion would be simple.

But it isn’t.

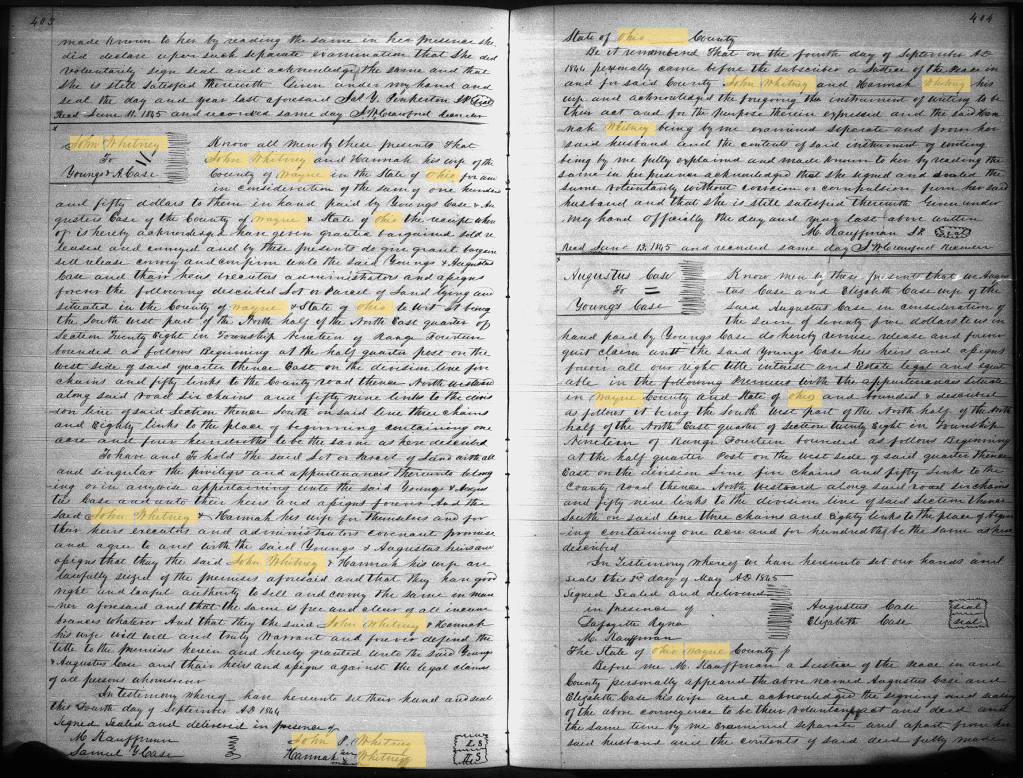

The Deeds: A Legally Identified Wife Named Hannah

In a deed, a wife is not named casually. She appears because she must relinquish her right of dower, and she is often examined separately to confirm that she is acting of her own free will.

John appears with Hannah as his wife in multiple land transactions:

On 4 September 1844 (recorded 13 June 1845), John Whitney and Hannah his wife sold land in Wayne County.³

On 13 September 1853, John P. Whitney and Hannah his wife conveyed land to Cornelius Paugh.⁴

On 18 February 1854, John P. Whitney and Hannah his wife conveyed land to Israel Layton.⁵

These are not isolated references. They establish a legally recognized wife named Hannah over a period of at least ten years.

By 17 December 1862, when John sold land again in Wayne County, no wife was named.⁶

Hannah was no longer living—or no longer his legal spouse—by that date.

Establishing That This Is the Correct John Whitney

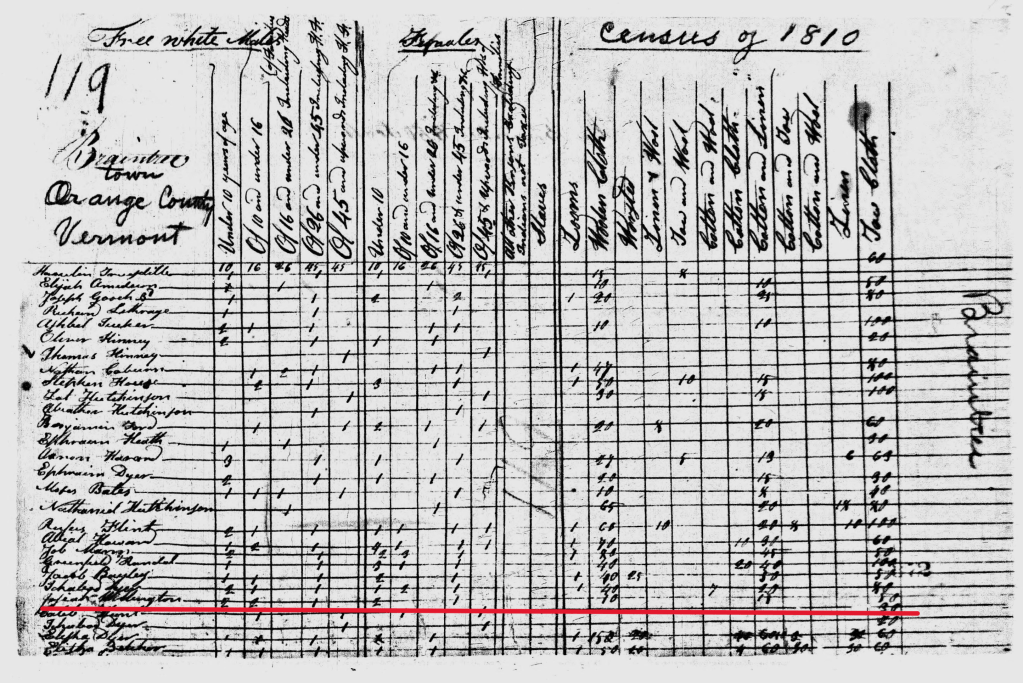

John’s father, Charles Whitney, died in 1836. His mother, Tamer (Pierce) Whitney, remarried Phillip Yarnell on 31 March 1840 in Wooster, Wayne County, Ohio.⁷

So when John P. Whitney appears in the June Term 1851 partition case with the Yarnell heirs, it confirms that these land and court records belong to the correct man.⁸

In the October Term 1851 case of Rinear Beall vs. John Whitney, the summons was served by leaving a copy at John’s residence “with his wife,” again placing him in a marital relationship at that time.⁹

The Negative Search

If the answer were in the usual places, this would not be a problem.

I have searched for:

- a divorce record for John Whitney

- a death record for Hannah Whitney

- a death record for Susannah Robison or Susannah Whitney

- any additional marriage for John Whitney

I have also looked for records that might name Nancy’s mother:

- guardianships for John’s children

- deeds involving his children

- death records for Nancy and her sisters

None of them identify a mother.

Could the Marriage Record Be Wrong?

One possible explanation is that the 1842 marriage record misidentifies the bride as Susannah rather than Hannah.

However, the record clearly names Susannah, there is a separate woman of that name in the 1850 household, and there is currently no record connecting Hannah to the Robison family.

That makes this a hypothesis—not a conclusion.

One Conflict, One Conclusion

Taken together, the records establish five things:

John Whitney is Nancy’s father.

He married Susannah Robison in 1842.

He had a legally identified wife named Hannah from at least 1844 to 1854.

Hannah and Susannah were two different women in the 1850 household.

The land and court records all belong to the same John Whitney.

What they do not establish is which woman was the mother of Nancy, Mary Belle, and Lucretia.

ThruLines does not resolve that conflict. The census does not resolve that conflict. The marriage record does not resolve that conflict.

So the only evidence-based conclusion is the same one I reached years ago—now with far better documentation:

The identity of Nancy J. Whitney’s mother remains unproven.

Footnotes

- 1850 U.S. census, Wayne County, Ohio, population schedule, John Whitney household.

- Wayne County, Ohio, marriage record, John Whitney and Susannah Robison, 18 August 1842.

- Wayne County, Ohio, Deed Book, John Whitney and Hannah his wife to Youngs & Augustus Case, 4 September 1844 (recorded 13 June 1845).

- Wayne County, Ohio, Deed Book, John P. Whitney and Hannah his wife to Cornelius Paugh, 13 September 1853.

- Wayne County, Ohio, Deed Book, John P. Whitney and Hannah his wife to Israel Layton, 18 February 1854.

- Wayne County, Ohio, Deed Book, John P. Whitney to Jonathan Potts, 17 December 1862.

- Wayne County, Ohio, marriage record, Phillip Yarnell and Tamer Whitney, 31 March 1840.

- Wayne County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas, partition case, June Term 1851, naming John P. Whitney and Yarnell heirs.

- Wayne County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas, Rinear Beall vs. John Whitney, October Term 1851.