If DNA can mislead, probate records rarely do.

After years of uncertainty about Frances “Fanny” Tolles, the answer did not come from genetic matches or online trees. It came from something far more old-fashioned: a thick, handwritten court file created after the deaths of her parents.

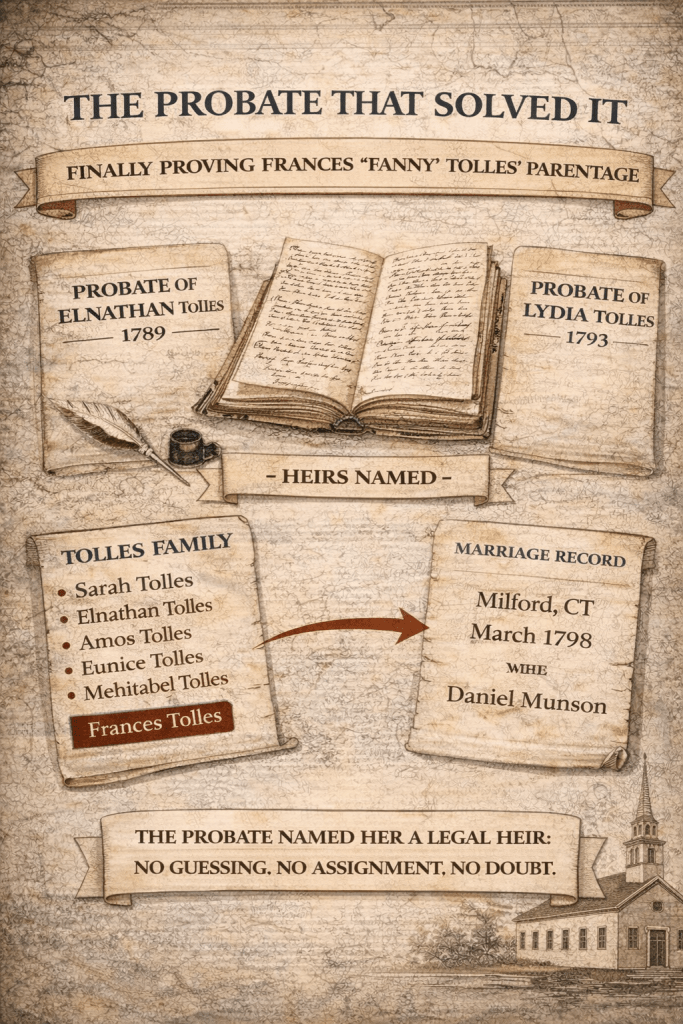

When Elnathan Tolles died in 1789, he left behind a widow, Lydia, and six children. Lydia died in 1793, and their estates were administered together. The combined probate file for Elnathan and Lydia runs more than sixty pages, filled with inventories, accounts, and distributions. It is not easy reading — but it is extraordinarily valuable.

Buried in that paperwork is the simple truth genealogists search for:

the names of their children as legal heirs.

Among those heirs is Frances Tolles.

That single fact matters more than any later genealogy or DNA match. Probate law in eighteenth-century Connecticut was precise. Only legitimate children or legally recognized heirs were entitled to a share of an estate. Frances was not a guess, a rumor, or an assignment. She was acknowledged by the court as the daughter of Elnathan and Lydia Tolles.

The probate does not tell us whom Frances married. It does not say “wife of Daniel Munson.” But it does tell us something just as important: Frances Tolles lived to adulthood and inherited as Elnathan’s child.

That eliminates all of the uncertainty that once surrounded her. There was not one Frances Tolles who belonged to Elnathan and another who married Daniel Munson. There was only one Frances — born in 1775, raised in the Tolles household, and alive when her parents’ estates were settled.

When that legal fact is combined with the Episcopal church records that show Frances (“Fanny”) Tolles marrying Daniel Munson in Milford in 1798, the identity becomes clear. The girl baptized in New Haven, the heir named in probate, and the bride in Milford are the same person.

This is how real genealogical proof is built. Not from a single perfect document, but from the way independent records fit together without contradiction.

DNA raised the question.

The probate answered it.

In the next and final post of this series, I’ll show why the Episcopal Church — not town records or DNA — was the quiet key that held this whole story together.

Sources

- Probate of Elnathan Tolles (1789) and Probate of Lydia Tolles (1793), Plymouth (Watertown) District, Litchfield County, Connecticut, combined estate file (66 pages), naming Frances Tolles among the heirs.

- Donald Lines Jacobus, Families of New Haven, vol. VIII (1932), Tolles family, listing Frances baptized 12 March 1775 and identifying her as “Fanny” who married Daniel Munson.

- Milford, Connecticut, Marriage Records, 19 March 1798, Daniel Munson and Frances (Fanny) Tolles.