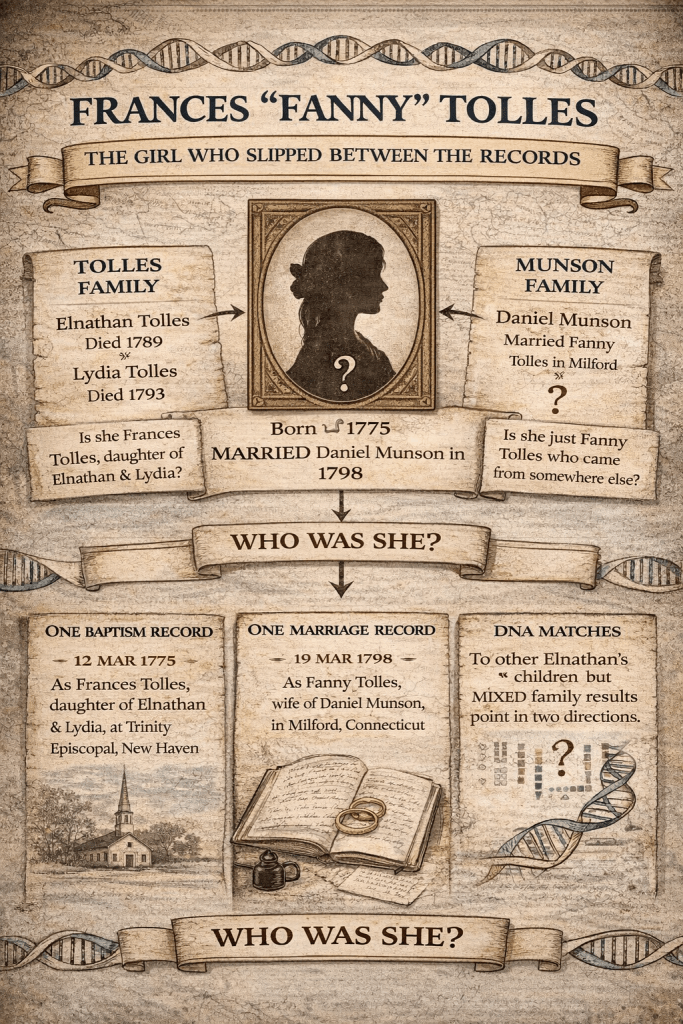

Genealogy often feels like assembling a puzzle — until you discover that one of the most important pieces was never cut to fit. That is what happens with Frances “Fanny” Tolles, the daughter of Elnathan and Lydia Tolles, and the woman who would later become the wife of Daniel Munson.

On paper, Fanny should be easy to find. She was baptized on 12 March 1775, just as the American Revolution was beginning. In the Episcopal records of New Haven she appears as “Frances,” daughter of Elnathan and Lydia Tolles.¹ But after that single entry, she seems to vanish.

Her parents lived in Northbury (later Plymouth), Connecticut, during the war years — a place where church and town records were scattered across jurisdictions and denominations. The Tolles family belonged to the Episcopal Church, not the Congregational churches that recorded most Connecticut vital events. As a result, many of Fanny’s milestones were preserved only in church books, not town ledgers.

Then her family fractured.

Elnathan Tolles died in 1789. Lydia followed in 1793. Their children were still young. Some were placed under guardianship, others went to live with relatives. The probate files confirm their identities as children of Elnathan and Lydia — but they do not track what happened to them afterward.²

This is where Fanny disappears.

By 1798, a Frances (or Fanny) Tolles married Daniel Munson in Milford, Connecticut — a town strongly associated with the Clark family, Fanny’s maternal kin.³ Yet nowhere in the marriage record are her parents named. There is no “daughter of Elnathan” to anchor her identity. She simply appears, gets married, and then moves on.

Later genealogies tried to solve this gap, but not all of them were confident. Early Tolles and Munson researchers knew that Daniel Munson’s wife was named Fanny Tolles, and they knew that Elnathan and Lydia had a daughter named Frances of the right age. But without a clear marriage record naming her parents, some writers hedged, quietly assigning her to Elnathan because she fit — not because a document said so.

That uncertainty lingered for generations.

In modern times, DNA added a new layer. A distant DNA match appeared to descend from another child of Elnathan Tolles, seemingly supporting Fanny’s placement in the family. But further research revealed a second, older connection through the Mix family, meaning the DNA could not be used to prove Fanny’s parentage after all. The evidence was real — but it pointed in two directions.

This is why I have over 64,000 people in my family tree. Not because I like big numbers, but because tiny errors in the 1700s ripple forward into the DNA era.

So who was Fanny Tolles?

Was she truly the daughter of Elnathan and Lydia?

Or was she “assigned” to them because no better answer existed?

To find out, we have to leave church books and DNA charts behind — and turn to something far more powerful: probate law.

Sources

- Trinity Church (Episcopal), New Haven, Connecticut, baptismal records, 12 March 1775, Frances Tolles, daughter of Elnathan and Lydia Tolles; abstracted in Donald Lines Jacobus, Families of New Haven, vol. VIII (1932).

- Probate of Elnathan and Lydia Tolles, Plymouth (Watertown) District, Litchfield County, Connecticut, 1789–1794, combined estate file, listing their children including Frances.

- Milford, Connecticut, Marriage Records, 19 March 1798, Daniel Munson and Frances (Fanny) Tolles; cited in The Munson Record and Milford town records.