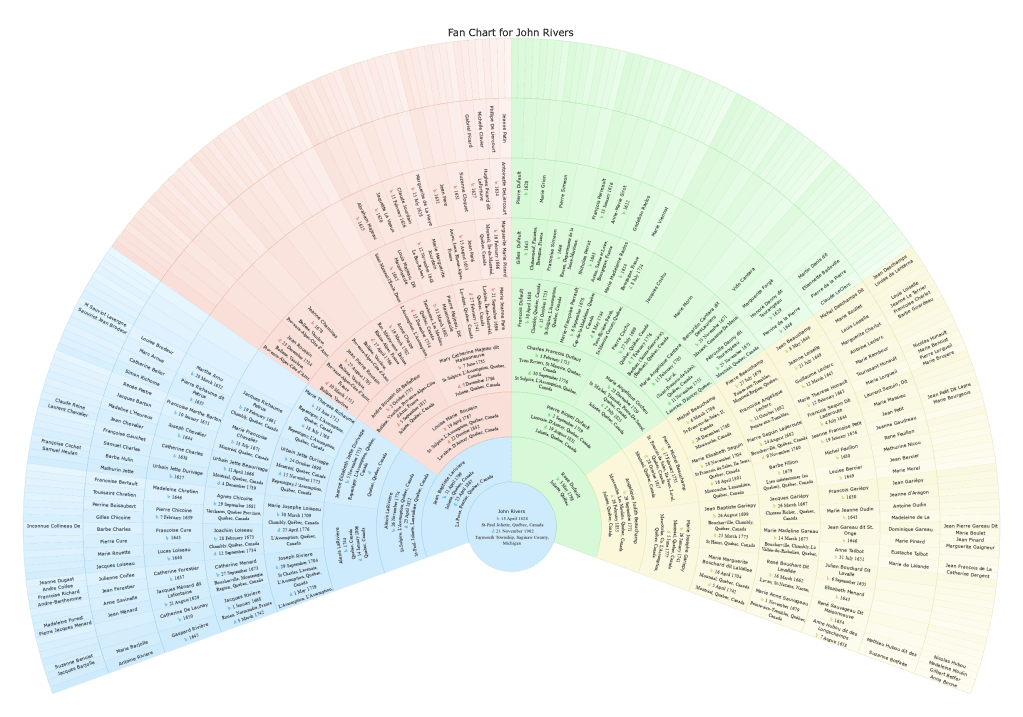

For many years, my second great-grandfather John Rivers was one of the most stubborn brick walls in my family tree. I knew when and where he lived as an adult, but his early life was completely undocumented. He appeared in Michigan in the early 1860s, married, and raised a large family—but nothing in U.S. records clearly revealed who he had been before crossing the border from Canada.

It took DNA evidence, careful work with French-Canadian church records, and a great deal of patience to finally reconstruct his origins.

A Man Who Appeared in Michigan

John Rivers was born in Quebec, Canada, in the late 1820s. Over the years, U.S. records reported his birth anywhere from 1824 to 1830, a common problem for 19th-century immigrants whose ages were often estimated. What was consistent was that he was Canadian-born.

In many U.S. census records, he was described specifically as “French Canadian.” That detail mattered: it pointed not just to Canada, but to French-speaking Quebec.

Long before DNA entered the picture, I found another clue. When I was a child, I discovered a handwritten note tucked into an old family Bible, written by my paternal grandmother, stating that John Rivers was born in Quebec. At the time, I had no way to verify it. Sadly, that slip of paper has since been lost. But years later, when I began working with census records, I realized something important: what my grandmother had written matched what the census takers had recorded decades earlier.

Two independent sources—one familial, one official—were quietly telling the same story.

By 1860, John had crossed into the United States. In 1862, he married Frances Jane Munson in Michigan. They settled in Saginaw County, where John worked and farmed while raising a large family.

Between 1863 and 1887, Frances gave birth to at least twelve children. Like many rural Michigan families of the period, they also experienced tragedy: two daughters born in 1868 and 1869 died in infancy, and a son, Franklin, born in 1874, died at age six.

Census records place John and Frances in Taymouth Township and later in Albee Township, part of the agricultural and lumber economy of mid-Michigan. By 1900, John was still living in Taymouth, surrounded by adult children beginning families of their own.

John died on 21 November 1902 in Taymouth Township, Saginaw County, Michigan, from broncho-pneumonia. He was buried two days later in Taymouth Township Cemetery. His Michigan death certificate, however, leaves both parents’ names blank.

Family Stories Without Proof

Two family stories followed John Rivers through the generations. One said he had come to Michigan as a Jesuit priest or with one. Another claimed he was part Native American.

These stories were preserved in family memory, but no documentation has yet been found to confirm either one. What has been discovered is that several of John’s ancestors and close relatives in Quebec were affiliated with the Jesuit order, which may explain how the priest story entered the family narrative—even if John himself was not a priest. The Native American claim, however, has not been supported by records or DNA.

The DNA Breakthrough

The real breakthrough came through genetic genealogy.

I tested in all the major DNA databases and had a male double first cousin test as well, giving us a broader pool of shared matches. His autosomal DNA produced connections I did not inherit by chance. Using results from Ancestry, 23andMe, and FamilyTreeDNA, I began building trees for our shared matches.

Again and again, the same French-Canadian families appeared.

Eventually, those matches converged on one Quebec couple:

Jean-Baptiste Larivière and Rose Dufault.

That gave me a working hypothesis. The next step was to find records.

How the “Dit” Name Led Me Down the Wrong Path

Early in the research, I found a baptism for Jean Beaudoin dit Larivière in 1824. It looked promising:

- Jean → John

- Larivière → Rivers

- The timing was close

What confused me was the “dit” name. In French-Canadian records, a dit name is an alternate surname used by a branch of a family. I initially misunderstood it and thought this might be my ancestor.

Once DNA evidence was added, it became clear that this child belonged to a different family line and was not my John Rivers. That realization kept me searching.

The Right Jean

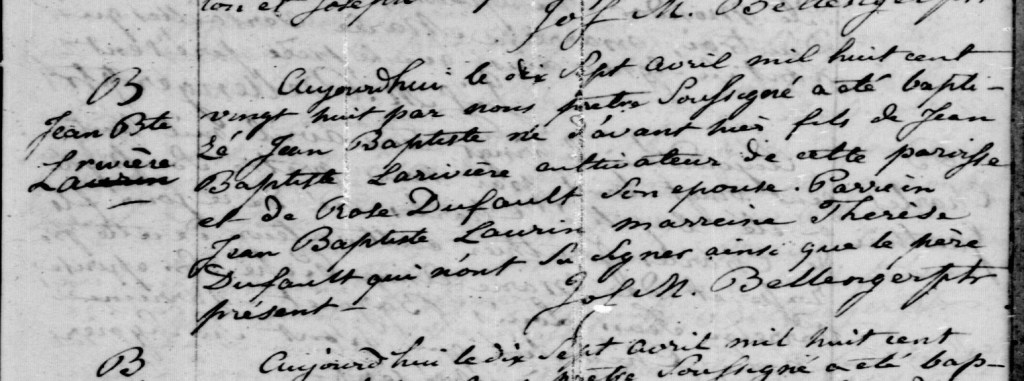

That search led me to a different baptism — this time simply Jean Larivière.

Aujourd’huy le dix sept avril mil huit cent vingt huit par nous prêtre soussigné a été baptisé Jean Baptiste né d’avant hier fils de Jean Baptiste Larivière cultivateur de cette paroisse et de Rose Dufault son épouse. Parrain Jean Baptiste Laurin marraine Thérèse Dufault qui n’ont su signer ainsi que le père présent. – J. M. Bellenger ptre

English Translation

“Today, the seventeenth of April eighteen hundred twenty-eight, by us the undersigned priest, was baptized Jean Baptiste, born the day before yesterday, son of Jean Baptiste Larivière, farmer of this parish, and of Rose Dufault his wife.

Godfather Jean Baptiste Laurin, godmother Thérèse Dufault, who did not know how to sign, as well as the father who was present. – J. M. Bellenger, priest.”

He was baptized on 17 April 1828 at Saint-Paul-de-Joliette, Quebec, born two days earlier on 15 April 1828, the son of Jean-Baptiste Larivière and Rose Dufault — the very couple identified by the DNA evidence.

The name fit.

The date fit.

And now, so did the DNA.

After adding Jean-Baptiste Larivière and Rose Dufault to my tree, DNA matches began appearing through ThruLines and shared match groups for their children, grandchildren, and extended family. While each match still needs individual verification, the genetic evidence lines up with the documentary trail.

There is no single record stating outright that “John Rivers of Michigan is Jean Larivière of Quebec.” His U.S. death certificate does not name his parents. But in genealogy, proof is built through converging evidence—and here, the church records, migration pattern, census data, family memory, and DNA all point to the same conclusion.

No Longer a Brick Wall

John Rivers is no longer a mystery man who appeared out of nowhere in Michigan. He was born Jean Larivière in Joliette, Quebec, in 1828, the son of Jean-Baptiste Larivière and Rose Dufault, part of a deep French-Canadian family whose lines extend back many generations.

His journey—from Quebec parish registers to Michigan farmland, from a French surname to an English one—was hidden for nearly two centuries. It was DNA, combined with traditional genealogy, that finally brought his story back into the family.