When we talk about Revolutionary War service, we often picture soldiers on the battlefield or officers directing maneuvers. But for many men in New Jersey, the war was fought on the roads — muddy, frozen, rutted roads that carried the lifeblood of Washington’s army. Few stories illustrate this better than that of John T. Wortman, born in Morristown on September 25, 1757, and later known in the records as the teamster who helped keep the Continental Army alive during its darkest winters [1]. His life offers a window into the logistical backbone of the Revolution, a side of the war we rarely talk about but absolutely should.

John Jr. grew up in a world already shaped by the long Dutch presence in New Jersey. His father, John Wortman Sr., remained rooted in Somerset County, but John Jr. came of age farther north, in the developing communities of Morris County. That shift in geography — a short distance on a modern map — made all the difference in the kind of service he would eventually render. While his father’s life revolved around Bedminster, John Jr.’s world centered on Morristown, Roxbury, and Chester, places that would become synonymous with the Continental Army’s winter encampments and supply struggles [1][6]. This geographic divide is one of the most important clues for genealogists trying to distinguish the two men.

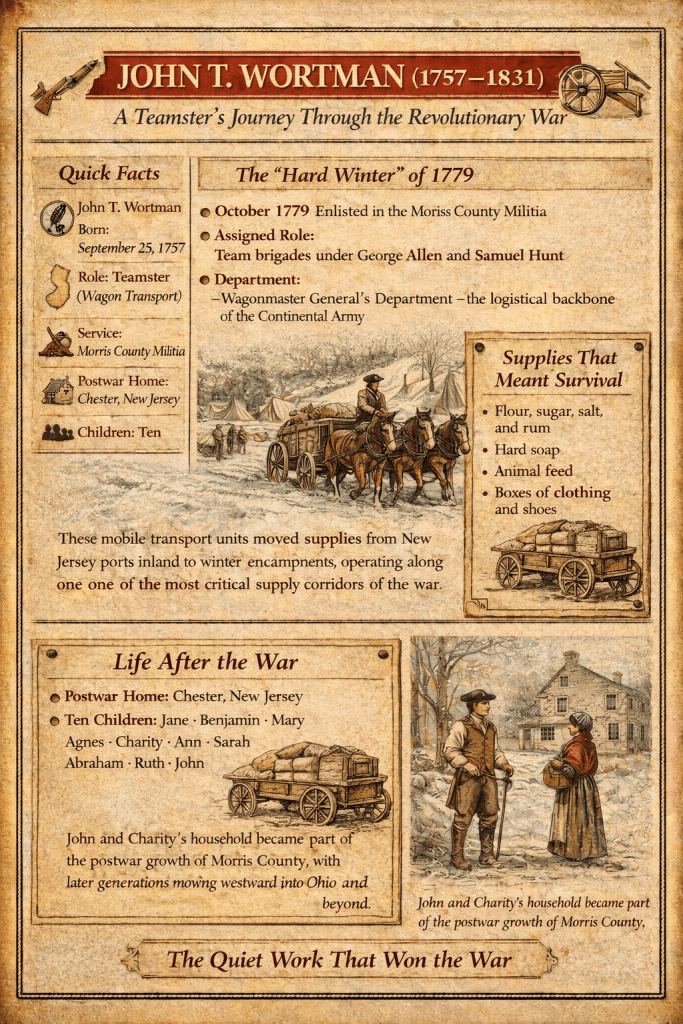

Enlistment During the “Hard Winter”

By the fall of 1779, the war had entered one of its most desperate phases. The army was preparing for what would become the infamous “Hard Winter” at Morristown, a season so severe that even seasoned soldiers later recalled it with dread. It was in this moment that John Jr. enlisted in the Morris County Militia [1]. His role was not that of a traditional infantryman. Instead, he joined the specialized team brigades — the mobile transport units that hauled food, clothing, equipment, and forage across New Jersey’s interior.

These brigades, led by George Allen and Samuel Hunt, operated under the broader umbrella of the Wagonmaster General’s Department, the logistical backbone of the Continental Army [1][10]. Their work was relentless. Supplies arrived by water at Lamberton, a small but strategically vital port just south of Trenton, where sea‑going vessels could unload their cargo. From there, men like John Jr. took over, guiding heavily loaded wagons northward through the state’s most important military corridor [1]. This corridor — stretching from Lamberton to Morristown and then into the Hudson Highlands — was one of the most strategically important supply routes of the entire war.

What John Jr. Carried — and Why It Mattered

The pension testimony preserved by his widow, Charity Messler, paints a vivid picture of what this work entailed. John Jr. hauled:

- Flour, sugar, salt, rum

- Hard soap and animal feed

- Boxes of clothing and shoes

These weren’t abstract “supplies”; they were the difference between endurance and collapse for the men stationed at Morristown, New Windsor, Pompton, Tappan, and even West Point [1]. Each load he carried represented a small but essential piece of the army’s survival. This is the kind of detail that helps us understand the daily realities of Revolutionary logistics in a way that battlefield reports never could.

The roads he traveled were not the smooth turnpikes of later centuries. They were often little more than dirt tracks, churned into deep mud by rain or frozen into jagged ridges by winter storms. Driving a wagon through such conditions required strength, patience, and a deep familiarity with the landscape. John Jr. had all three.

The Condict Papers: Witnesses Who Remembered Him

One of the most valuable pieces of evidence for his service comes from the Lewis Condict Papers, a collection of notes taken between 1833 and 1837 from pension applicants and their neighbors. In these papers, witnesses such as William Todd confirmed John Jr.’s enlistment in October 1779 and his work as a teamster in the Allen and Hunt brigades [12]. These testimonies, combined with Charity’s pension application (W100), firmly anchor him in Morris County and distinguish him from his father, whose service belonged to Somerset County [1][6].

This kind of corroboration is gold for anyone doing serious genealogical reconstruction, especially when dealing with repeated names across multiple counties.

Life After the War

After the war, John Jr. settled permanently in Chester, where he and Charity raised a large family of ten children — Jane, Benjamin, Mary, Agnes, Charity, Ann, Sarah, Abraham, Ruth, and John [1]. Their household became part of the post‑war growth of Morris County, and later generations would carry the family westward into Ohio and beyond.

His death on May 19, 1831, closed the chapter on a life defined not by battlefield heroics but by the unglamorous, indispensable labor that kept an army functioning [1]. His story reminds us that the Revolution was not only fought with muskets and bayonets, but with wagons, wheels, and the steady determination of ordinary men who understood that their work mattered.

Sources

- John T. Wortman (1757–1831) | WikiTree – https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Wortman-6

- Workman Family History Americana –

https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~n3kp/genealogy/workman_hist(freepages.rootsweb.com in Bing) - Collections of the New York Historical Society – Internet Archive

- Centennial History of Somerset County, NJ – Genealogy Trails

- WorkmanFamily.org – Wortman Genealogy

- A Rare Opportunity – National Society Sons of the American Revolution

- Somerset County Historical Quarterly – Internet Archive

- WikiTree G2G: Revolutionary War Ancestors

- Essex County Rev War Project – Plainfield Public Library

- Geertjie (Messler) Wortman | WikiTree – https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Messler-2

- New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, Vol. 9 (1924) – Internet Archive

- Lewis Condict Papers, 1833–1837 | New Jersey Historical Society

- Clarke County Historical Association Proceedings, Vol. 17